The following transcript is from a video recorded of the artist discussing the portrait painted of his partner over a weekend. The artist sits in a corner of his studio by a window sill. Dressed in a grey suit and white shirt. On the window sill sits a small teddy bear dressed in a blue and white outfit that the artist purchased in Berlin last summer.

I met him at a drag show. It was a Thursday night. At a place called “Feinstein’s at 54”. In Midtown. The performer was named Flotilla De Barge (who happens to be Chris’ uncle). The romance began that night and it was pretty much a fairy tale romance. Everything you hear and see but you pretty much don’t believe really happened. We looked at each other across the room and just started staring each other in the eyes. I had a glass of wine. He had tequila. We looked at each other. Looked at the show. Looked at each other. Pretended to look at the show. And all of a sudden, this gentleman raised his glass to me and in return I raised my glass to him. The artist picks a glass up from the floor and raises it.

We spoke that night and, um, began dating.

Regular dates. Regular dates like you see in the movies. Dinners. Movies. Um… (long pause). We didn’t sleep together. For quite a while. We just…we just dated. And, like a fairy tale story, when we did finally, uh, become intimate for the first time, it was on the 4th of July…fireworks baby. The artist tilts his head to the side and raises an eyebrow as he says this and not for the first time we see that there is a touch of cockiness in him.

And we were inseparable ever since. And I knew right away, um, that this was the person who I wanted to spend the rest of my life with. I’ll drink to that. The artist takes a swig of his drink.

I heard two friends of mine tell me the tale of their engagement. These two friends were married for twelve years already. And they told me that they were engaged six months after they met. Well, not being one to be outdone (head tilts again) I asked Chris to marry me five months after we met. So now we are engaged. Artist holds up hand to show ring. It’s a nice ring.

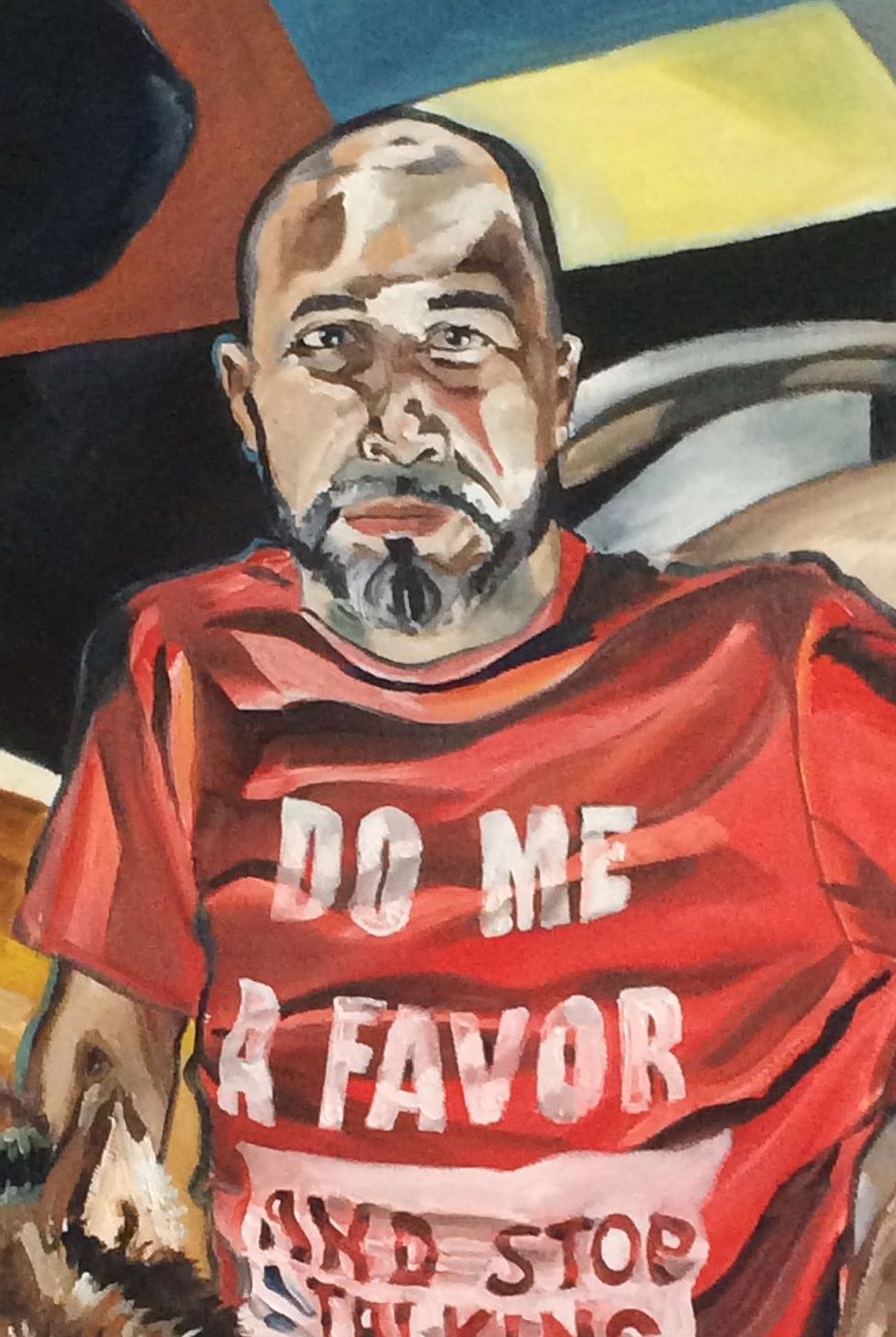

Of course we…oh…okay…I’ll drink to that. In an attempt at humor, the artist clinks his glass with a glass set by the teddy bear in the blue and white outfit. This was obviously set-up for the interview. He continues…of course, now that I have a partner, this is going to be the object of much of my artwork and my portraiture because even though a lot of my portraiture is geared toward people and exploring people, it’s also very biographical and, since this is the person in my life, this is the person who I will be painting intermittently and studying for a life time. So that’s how this portrait came about.

I think when people think about me painting portraits of people, and particularly people I am intimate with, I think they think it’s like the scene from “Titanic”: very kind of romantic and, um, and beautiful and, um, lustful. Artist begins unbuttoning his jacket. Um. It’s not. Long pause. At all. Artist is now shifting in his seat and removing the jacket revealing a tight-fitting grey vest and white shirt.

So I knew I had to do this blog. I knew I had to get a piece of work done. And I hadn’t been working. So I asked Chris, I said, Chris, listen, I want to paint your portrait, I’ve got to paint your portrait this weekend, it’s gotta be this weekend. Because him and I…we will spend weekends going to the movies, shows, in bed (loaded pause), going to this place for dinner or that place for dinner. Um. So I knew the kind of mode we got into—if I didn’t put my foot down—that portrait was not gonna happen and I wouldn’t have a new piece of work for this blog. So I put my foot down and I said, “Chris!” artist throws jacket down to the floor. This is a performance. “I have to paint you this weekend”! and he said, “of course”.

So we set it up and I set up a time schedule. I said we are going to do it for these hours on Saturday and these hours on Sunday. Everything was fine. However. Friday night we went to a concert. In Brooklyn. King’s Theater (beautiful theater by the way. If you’ve not been to King’s Theater, you’ve gotta go see King’s Theater. It is gorgeous inside). So we’re sitting in the concert. And we’re making small talk as usual. We’re…we’re very much talkers. We’re always talking to each other. Artist forms two puppet hands talking to each other and then sniffles. And, um, he says something and I’m not going to tell you what he said.

Because that would be petty and it’s really none of your business.

But he says something that—and you’ve all felt this before—it may not be a big thing, that thing that someone says, but it triggers something inside of you (long pause) that brings out the worst in you. So we’re at this concert and Chris is sitting next to me and he says this thing (arms open wide as if to present “this thing”). And I am triggered. And then the show comes on a second after I’m triggered. Artist stops to refill his glass and we notice that he is filling his wine glass with a bottle of Arizona Green Tea. He is not taking this seriously. Or is he not taking his own story seriously? Is the story true?

So I’m watching the concert. Fuming. Trying to calm myself down. Because I want to have a nice weekend and I gotta paint Chris. Artist pauses to “refill” the teddy bear’s glass.

So, the concert ends and I’m trying to recover…you’re welcome (this is said to the bear). And I’m trying to regain my composure. I’m working my way towards it. I’m working my way towards it. I’m working my way towards it.

There’s a line. There’s a line in Paradise Lost by John Milton and the line pretty much it’s it’s it’s, it’s, ah, it’s, ah, talking about Lucifer. Artist reaches for the book which is conveniently at hand. Talking about Lucifer and how…and how he can’t get out of himself and how he can’t get out of, uh (artist buries face in his free hand) and how he feels…stupid…for trying to, uh, overthrow God. And he even misses God. He misses God…(Milton’s a genius). But he can’t get out of his feelings. Artist begins to read from the poem:

“Upon himself horror and doubt distract his troubled thoughts and from the bottom stir the Hell within him/ for within him Hell he brings/ and around about him nor from Hell one step can fly nor from change of place”

Artist throws book on floor.

You know what that means?

Long pause

That’s when you’re so furious that you can’t get out of it. When you take this step (artist points to his right) that’s Hell. When you take a step over here (artist points to the left of him) that’s Hell. When you take a step back. That’s Hell. The Hell is within you. The Hell is around you. And you’re carrying it with you and, ladies and gentlemen, I was carrying Hell with meeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee at that concert.

But I had to get over it. Because I had to paint this portrait.

So. I’m working on it, working on it, working on it. The next morning I try to talk to him a little about what triggered me and trying to get artist begins rambling in non-sense words with his tongue out as though exorcising a demon.

Fine. Good. Time for the portrait. Artist claps his hands. So. I’m painting the portrait and I’m seeing that, uh, Chris is (long pause)…He adores me. He loves me. Oooooo…does this man love me. It is very difficult for him to ignore me when I’m in his presence. And what I mean by that is, he was laying on the couch (as you see in the portrait) and he was watching “Empire”. Um, um, some episodes that he DVR’ed. And he’s watching “Empire” and, and, and I feel like I have to watch it with him; it’s over here (artist indicates his left side) and he’s over there (artist indicates a space in front of him) and the canvas is over there (artist indicates a space to his right) and, uh, he’s he’s he’s constantly needing my feedback and my conversation which is a beautiful thing but I can’t really kind of focus (artist starts juggling invisible balls) on the portrait.

Usually I’m used to people talking to me and having a conversation with me but it seemed like the conversation he was trying to have was geared toward what was happening on the screen (artist indicates his left side). So I had to pay attention to him, pay attention to the TV show, and pay attention to what I was doing.

Now, I managed it. I managed it, right? Boom, boom, boom, boom. I’m doing it. Then all of a sudden, Chris takes his T-shirt (artist grabs a white T-shirt close at hand. Obviously things have been strategically placed about him for illustrative purposes) and he starts laying there like this:

Artist holds the white T-shirt to his nose. Tilts his head down. And looks up with puppy-dog eyes.

Now, Chris has asthma, Ok? And I use oil paint. So, what I was getting from him was that the medium that I use (artist begins unbuttoning his vest) has a very, very, very strong smell and it was getting to him. And of course (artist peels off vest) I reacted—inside—irrationally. And when I saw him do this artist repeats T-shirt move that piece of me inside of me just screamed, “PLEASE…GIVE ME A BREAK. YOU KNOW I NEED TO DO THIS. YOU KNOW THAT THIS IS MY WORK”

As the artist says all of the above he moves from peeling off his vest to snatching a katana off the bed, unsheathing it, and pointing it at the camera. And then the artist softens and allows the katana to float in his hand softly.

But you can’t do that. You can’t be like that. The man is sick. He has asthma! You can’t blame him for that. C’mon. And I didn’t. Artist sheathes sword and places it across his crossed-legged lap. I just said, “you know what, Chris? I think that I have to, um…stop working”. And I said it very calmly. And I started moving the pieces out of the room. Throwing out the medium so that he didn’t have to smell it anymore. Because I’m a good person. Long pause as artist smiles maniacally and shifts in seat and slowly whispers to himself, “I am. I am”.

So I moved stuff out of the room and I was fine with it and everything was good. I kind of wanted him to say “no, baby. Let’s keep going. I’m fine”. But that’s me being selfish.

So. It’s time to do it in the, uh, the following day. On Sunday we reconvened and we pick up the portrait, um, where we left off. And he is, um, laying on the couch after, after a little coercing (head tilt). So everything’s going great. I’m working: boom boom boom. I love the way it’s coming out. I love the palette I’m using. And then, um, sorry…artist takes a sip of iced tea…and then he starts coughing.

Now of course the irrational part of me that needs this painting done is going ape shit. But the rational part who loves my fiancé (artist holds up ring) says, “Peter, get this stuff out of the room”. And so I did. So I got the canvas and the medium and the pallet and the brushes and everything, I got it out of the room, I put it in the next room and I waited for a few minutes to see if that was enough. Artist has noticed that his shirt is sticking out of the sides and begins tucking it in. Sorry, this is bothering me. I’m a little vain. Artist turns to the bear and tells it to shut up.

And he stopped coughing. To wit…as he watched some movie…”SAW?”…not the first one…I don’t know, I don’t watch them. As he watched “SAW”, I would paint (indicates his left side with the katana) run back to the scene of him in the other room (indicates his right side with the katana) try to remember the pillow in my mind and what it looked like, run back and paint that pillow or, like, the line of that pillow. Go back and try to remember what the desk looked like (katana to the left) go back, paint the desk (katana to the right) check it (katana to the left) check it (katana to the right). And I did that for the rest of the painting. The floor. The couch. Most of the pillows. The mirror.

Um…so it was very difficult.

And again, I think a part of me, the very selfish part wanted Chris to protest. I wanted him to…to…to be willing to die for my art. But that’s not nice. And that’s not fair. And that’s not love.

Long pause

The painting was finished. Artist puts the katana down, behind him. And it looks great. I loved it.

I was afraid that, years from now when I look back at that painting, (head tilt), I am going to think of all the negative things that happened that weekend; how I was triggered at the concert; um, how I couldn’t get myself out of it; how I felt like I wasn’t being supported with my work.

But its three days since the painting and I have to say the thing that I’m going to remember when I look at that painting is, I think, part of the key to love. And that is that, when you decide that you are going to commit to someone and make someone your life partner, there is no longer a “you”. It is not about your goals, what’s important to you, what you need to get done. It’s about the well-being of the relationship and the well-being of your partner.

And everything else is second to those two things.

And so what I want to remember is, I want to remember having to stop. I want to remember having to run back and forth in order to finish the painting so that my partner was well and comfortable (head tilt). I want to remember his sacrifice and I want to remember my sacrifice. And I want to remember that I did it gladly. Artist looks back at the katana. OK, not gladly…at the time: not gladly at the time. But in retrospect, I did it gladly.

And I learned a lesson.

My art is my art. My goals are my goals. And the question that I have to ask when I’m pursuing art and pursuing my career in art is, “hey, hey, hey, hey”, artist holds up finger to camera, “What’s love got to do with it?”

Because you’re in love. And that comes first.

Artist turns to bear: You like that? I thought that was good. I think we can stop now.